Ontario: The Geological Story of The Historic Pakenham Stone Bridge

GPS Location: 45 20 08.32N; 76 17 13.59 W

Figure 1: The historic Pakenham bridge is 5-span, stone bridge, located in the village of Pakenham (MIssissippi Mills), Ontario, is reported to be the oldest, active five-arch stone bridge in North America. Photo by Andy Fyon, Sept 12/17.

Historic Pakenham Stone Bridge - One Of North America's Rare Five-Span Stone Bridges

The historic Pakenham, five-span, stone bridge (Figure 1) is reported to be the only one of its kind in North America. There are other five, or more, stone span bridges around the world, including: a) one crossing River Avon chalk river at Amesbury, Wiltshire, England; b) the spectacular, multi-span Royal Border Bridge, which crosses the Tweed River between the towns of Berwick-upon-Tweed and Tweedmouth in Northumberland, England; and c) one at Christchurch, Dorset England. There is a five-span stone bridge at Avon, New York. There are likely others and I did not carry out an exhaustive search. Regardless, in Ontario, the five-span Pakenham stone bridge is well worth the visit. It is listed as one of the Seven Wonders of Lanark County.

Is there a geological story behind this old historic bridge? Simply stated - yes. Afterall, the bridge is made of stone!

Basic Bridge Engineering

While I am not a structural engineer, there is a general engineering principle that arch structures are very strong and visually pleasing. For that reason, arches were commonly used in older construction works before modern concrete and reinforced steel had been "invented". But, regardless of form, an incorrectly built arch can quickly collapse as gravity pulls it down!

The Pakenham bridge was built in 1903, or 1901 depending on source, and spans the Mississippi River in the town of Pakenham (now part of Mississippi Mills), Ontario. The bridge measures 82 metres long (268 feet), 6.7 metres (22 feet) high, 7.6 metres (25 feet) wide. Each of the five arches are about 12 metres (40 feet) wide. The piers are each about 2.4 metres (8 feet) thick. The bridge is made from limestone rock (Figure 2). The largest limestone block in the bridge is about 2.7 metres (9 feet) long and about 0.8 metres (2.5 feet) square, and weighs over 4.5 tonnes (5 tons).

Figure 2: A photo of the limestone blocks that were used to construct the five-span, Pakenham stone bridge, looking to the east across the Mississippi River. Photo by Andy Fyon, Sept 12/17.

In 1984, the original bridge was carefully disassembled so that it could be strengthened and reassembled to accommodate modern traffic volumes and loads. The bridge needed to be brought to modern engineering standards, because, when the bridge was originally built, there was neither the volume nor the vehicle weight that the bridge sees from modern traffic today. Cars and trucks were rare in the early 1900's!

Geology Of The Bridge

The Pakenham bridge is constructed of massive to thinly bedded limestone rock (Figure 2). Limestone is a sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate occurs in the form of a mineral called calcite. Limestone was a favourite construction material for stone structures in southern Ontario because under ideal conditions, some limestone has the following engineering properties that enables it to stand up well to abrasion and freeze-thaw:

is a strong, dense rock;

is free of tiny holes that are called pore spaces; and

does not react to salt applied to prevent road icing.

Limestone is also locally abundant and is much easier to mine compared to other rock types like those that are found in the Canadian Shield. This was particularly important in the early 1900's when mining equipment and explosives were still primitive compared to today. Limestone does not put the same wear and tear on mining equipment or the vehicles used to transport it. Also, in the early 1900's, there were many stonemasons available who were skilled in the art and science of working with limestone to build structures. All of this meant that the limestone was relatively easy to quarry out of the ground, shape into the required blocks, transport to the bridge construction site, and finish to ensure the pieces fit together securely.

Local Geology

In the immediate area of the Pakenham bridge, the local geology likely influenced the selection of local limestone as the construction material of choice. The Pakenham village area lies along the boundary between are area of old Canadian Shield rock to the west and younger Paleozoic limestone rock to the northeast (Figure 3). The old Canadian Shield rock consists of ancient marble (light blue on Figure 3), ancient volcanic rock born of volcanoes (green on Figure 3), and granite that began as partially melted rock that froze before reaching the surface of the Earth (pink on Figure 3). In this area, the ancient Canadian Shield rock is about 1 billion years old. To the northeast of the Canadian Shield rock lies younger Paleozoic rock that consists of sandstone and limestone rock (yellow and blue respectively on Figure 3). The younger Paleozoic rock lies like a blanket on top of the old Canadian Shield rock. In this area, the younger Paleozoic rock is about 580 to 450 million years old.

Figure 3: General geology of the Pakenham area. This geology map is created using the on-line OGS Earth application and Google Earth. The old, one billion-year-old Canadian Shield rock consists of: a) ancient marble, coloured light blue on the map; b) ancient rock born of volcanoes, coloured green on the map; and c) granite, coloured pink on the map. The younger, 500 to 450 million year old Paleozoic rock lies to the northeast of the Canadian Shield rock and consists of: a) sandstone, coloured yellow, which lies directly on top of the Canadian Shield rock; and b) different types of limestone, coloured dark blue and light blue. Bedrock geology assembled from OGS Earth (https://www.mndm.gov.on.ca/en/mines-and-minerals/applications/ogsearth/paleozoic-geology).

The younger Paleozoic sandstone rock (yellow on Figure 3) is made up of sand-size quartz grains that are held together, or cemented, by quartz cement. Geologists call this the Potsdam or Nepean sandstone. It formed about 500 million years old from debris created when the Canadian Shield rock was broken into tiny pieces by geological weathering processes. Based on features preserved in the rock, geologists conclude that much of the sandstone was laid down as a blanket from a ancient rivers called a "braided river".

Different types of Paleozoic limestone lie on top of the sandstone (dark and light blue on Figure 3). This younger limestone rock formed initially as a limy mud, which included dead marine animals, that fell to the bottom of a warm, subtropical ocean. That subtropical ocean covered this part of Ontario about 500 to 450 million years ago. The modern day Caribbean ocean is a good modern analogy for the type of ocean that covered the land about 500 million years ago. As the limy mud was buried deeper and deeper, it slowly changed into rock. Just as the sandstone has a special name, so too does the limestone rock. A detailed discussion of all the special limestone names is beyond the scope of this note; however, much of the Paleozoic limestone that was used to build the bridge, coloured dark blue on Figure 3, appears to belong to what geologists call the Bobcaygeon Formation. That name is based on information illustrated using the OGS Earth application. Geologists assign and use Formation names to distinguish between different rock layers based on unique or characteristic features.

A Marine Transgression

I have painted a very simple picture of the formation of the younger sandstone and limestone. But, in reality their history was more complex. The transition from sandstone to limestone tells a story of rising sea level relative to land about 500 million years ago. The sequence moving from sandstone into limestone tells geologists that the land was first exposed to air. Rivers washed across the land depositing sandy deposits. Slowly the seal level of the subtropical ocean rose and the sea began to flood the land. The shoreline would have moved to higher ground. Large parts of the old Canadian Shield would have stuck out of the sea as islands and large land masses. The conditions at that time changed from one dominated by surface rivers to one dominated by a shallow sea. Geologists call this change a marine transgression. The rising sea level could have been caused by the land sinking or the filling of an ocean basin by sea water. This is part of the story about the "Ontario Beneath Our Feet".

Where Was The Limestone Quarry?

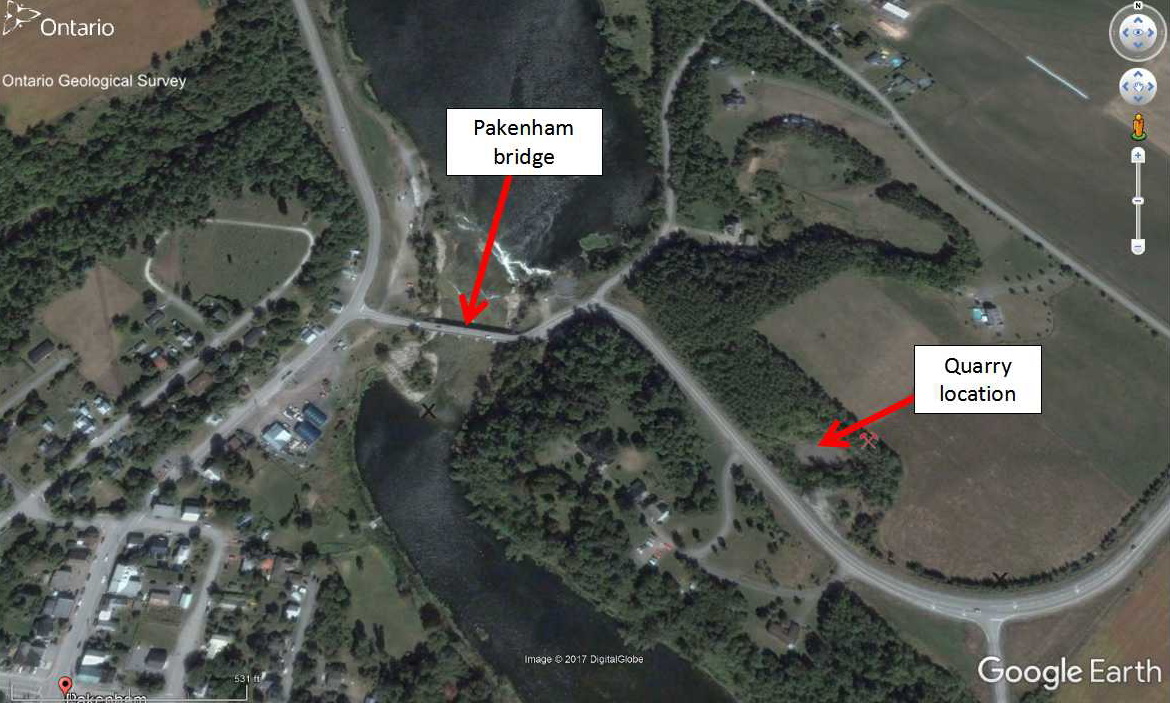

An old, inactive limestone quarry is located on the east side of the Mississippi River, very close to the Pakenham bridge, about 0.3 km (0.2 miles) away along Highway 20 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The location of the possible source rock quarry for the Pakenham five-span stone bridge is located east of the Mississippi River, about 0.3 km (0.2 miles) along Highway 20. The location of the bridge and quarry are highlighted. Image created from Google Earth.

I have assumed this is the quarry from which the limestone was cut and used to build the Pakenham stone bridge (Figure 5).

Figure 5: An old, abandoned quarry, located east of the Mississippi River, appears to be the source of the limestone rock used to construct the Pakenham five-span stone bridge. I have assumed that the limestone exposed in the quarry belongs to the Bobcaygeon Formation, based on data from OGS Earth geological application. Photo by Andy Fyon, Sept 12/17.

The limestone exposed along Highway 20, beside the old quarry, shows layers up to 40 or more cm thick (Figure 6). Geologists call these layers bedding. Some beds are blocky, while other beds are smooth. Each bed was laid down during a period of time when conditions in the ancient subtropical sea remained the same. Sudden, periodic changes in the conditions in, and around, the ancient sea resulted in the deposition of a slightly different material as a new bed on top of earlier beds. This creates a rock with successive beds, one on top of another.

Figure 6: An example of the limestone that is exposed along Highway 20, adjacent to the quarry that appears to have been the source of the limestone rock used to build the Pakenham five-span stone bridge. I have assumed this rock along Highway 20 is representative of the limestone rock that was quarried to build the Pakenham stone bridge. Photo by Andy Fyon, Sept 12/17.

The old limestone quarry occurs on a ridge. The ridge location would have added to the appeal of using that local limestone rock because: a) it would have been easier to cut the limestone rock out of an exposed ridge that was not covered by soil; and b) it would have been easier to transport the limestone blocks, extracted from the quarry, downhill to the bridge construction site. I speculate, but it is possible that the ridge was created by much greater water flow from the ancestral Mississippi River, during the time immediately after the last ice age, about 15,000 years ago. That greater water flow would have eroded and worn away the limestone rock as it cut the river valley.

Fossil Hunt

Do you know what a fossil is? A fossil is the preserved remains of plants or animals. Did you know that you can actually see different types of fossils in the rock close to the Pakenham bridge? If the water level of the Mississippi River is low, carefully walk out onto the flat rock that is exposed on the upstream side (south) of the bridge, by the small park. Look closely in the rock for fossils. How many can you find. Are they all the same? There is one long, really cool, fossil (Figure 7). There are other fossil types in this rock. Can you find them?

Figure 7: Cephalopod fossil exposed in the flat limestone rock that occurs immediately up-stream from the Pakenham bridge. The coin in the middle of the fossil is a Canadian dollar coin, used for scale. Photo by Andy Fyon, Sept 12/17.

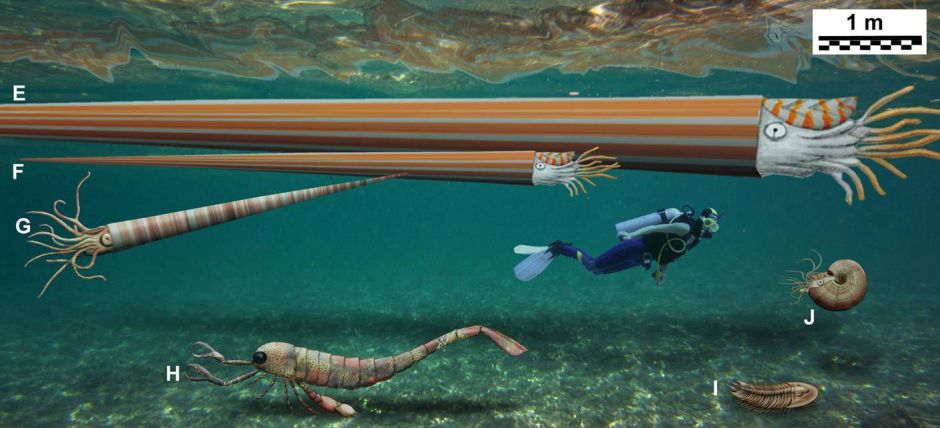

This long fossil appears to be made of narrow segments. This is a body fossil of a marine animal that lived about 480 million years ago in the subtropical sea that covered the land we now call Ontario. The animal grew to a large size, much bigger than the fossil preserved in the rock (Figure 8) and it was the top predator in the subtropical sea! Geologists call that ancient animal a Cephalopod. Believe it or not, this fossil is an ancient relative of modern-day octopus and squid.

Figure 8: A cartoon that illustrates the shape and size of an ancient Cephalopod. The large Cephalopod labeled "E" lived at about the time the limy rocks were forming at the bottom of the ancient sea that covered the land we now call Ontario, about 450 million years ago. For the explanation of the other labels, please refer to the original source of the image: Friedrich-Alexander-Universität

The Cephalopod fossil is the preserved shell of that the marine animal used as its home. The remains of the animal are not preserved - only its shell. The animal body rotted away or was eaten by scavengers shortly after its death and is not preserved. The animal lived in the large, open end of the shell. The animal's feet, or tentacles, extended out of the open end of the shell. To rise in the water, the Cephalopod would pump air into a special tube within the shell called a siphuncle. To sink, the Cephalopod would remove air from its siphuncle. To move forward, the Cephalopod would blast a jet of air out the back end of the siphuncle. This is how the Cephalopod rose, sank, or moved forward in water - just like a modern submarine. There are other fossil types in this rock. Can you find them?

Who Would Have Guessed?

When you visit the Pakenham, five-span, stone bridge, pause and think about the many people who worked to cut the rock out of the quarry, moved that rock to the Mississippi River, and carefully built this amazing engineering feat back in 1901 or 1903. That was a long time ago. Then cast your eyes to the rock just up-stream of the bridge to the Cephalopod fossil. That predator animal lived about 480 million years ago and is preserved in rock used to build the bridge. Who would have guessed that the story of the Pakenham five-span stone bridge is a really old one - about 480 million years old. That is just one small part of the story about the "Ontario Beneath Our Feet".

Other Resources

Here are some other resources to check out that describe and illustrate the Pakenham, five-span stone bridge:

a) Andrew Donaldson: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_QuZHEZyydE

b) Nick Daze: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWX2ura94zY

c) Brick Fistnar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hsef25pmZI

Have A Question About This Note?