Pingos - Pingo Landmark, Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada

The area around Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest territories, Canada, is world renowned for pingos. What are pingos, you ask? In this note, I describe what a pingo is and how it forms.

By the way, you can follow this link to see one of my YouTube videos entitled “Pingos - What Are They?”

What Does The Word Pingo Mean?

The word “pingo” is an Inuviat word for small hill, but it is not just any small hill. A pingo is a hill that has an ice core. Now, if you look at the pingo hill (Image 1), you wont see the ice, because a layer of vegetation covers the ice core. That vegetation consists of the typical plants that grow on the subarctic tundra.

Image 1: This geological landform is the Ibyuk Pingo, located in the Pingo Canadian Landmark (Pingo National Landmark), near the community of Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada. Ice occupies the core of the pingo. The pingo is covered by an insulating blanket of tundra vegetation, which keeps the ice core from melting. Image composed by Andy Fyon, June 18, 2019.

Pingo Types

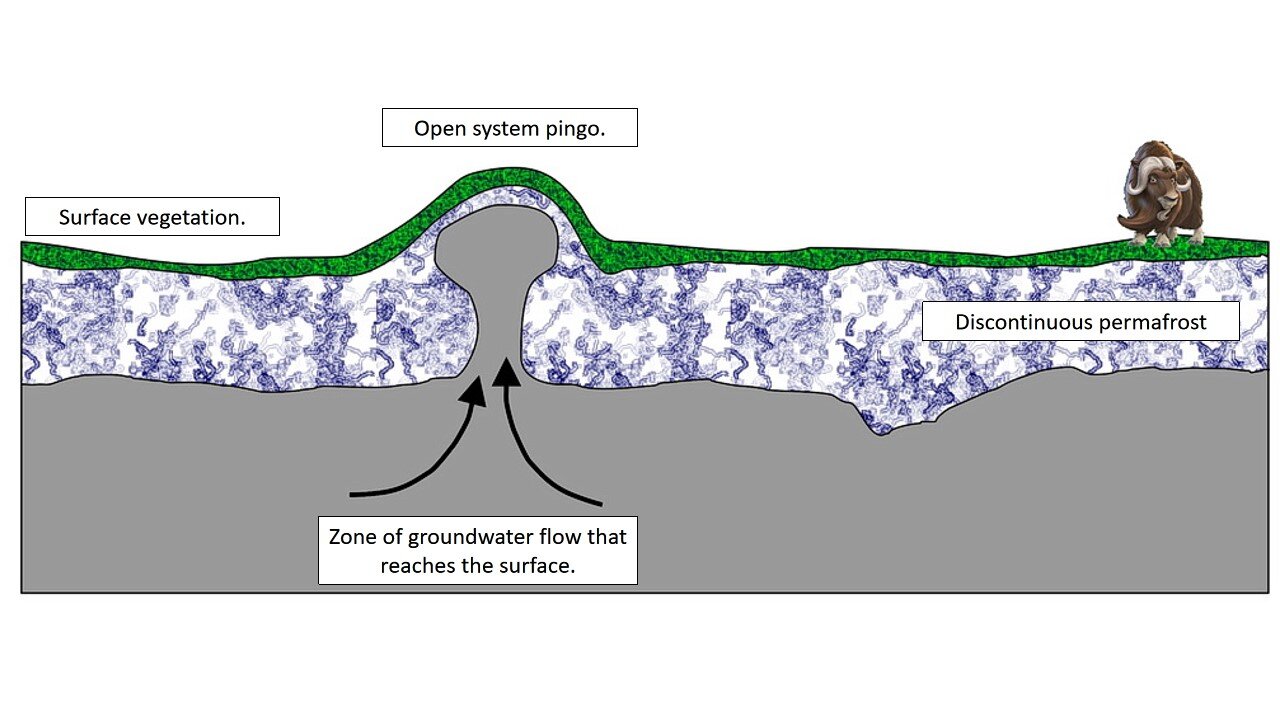

Scientists see two different types of pingos: a) closed system pingos, which form in areas of continuous permafrost, particularly in the footprint of a drained lake (Image 2); and 4) open system pingos, which are typical of the boreal forest, where discontinuous permafrost occurs (Image 3).

Image 2: Cartoon of an closed system pingo, where the pingo grows vertically when water-saturated muck freezes from below and from top down, in an area of continuous permafrost. Cartoon by E. Ginn, April 18/21

Image 3: Cartoon of an open system pingo, where groundwater flows in an area of discontinuous permafrost. Cartoon by E. Ginn, April 18/21

The pingos around Tuktoyaktuk are closed system pingos (Image 2). That is, they formed in a region of continuous permafrost, frequently in the foot print of a drained, or partially drained, lake. These closed system pingos are easy to pick out because of their mound shape on the otherwise flat tundra landscape around Tuktoyaktuk (Image 1).

In this note, I focus on closed system pingos.

Pingos Near Tuktoyaktuk

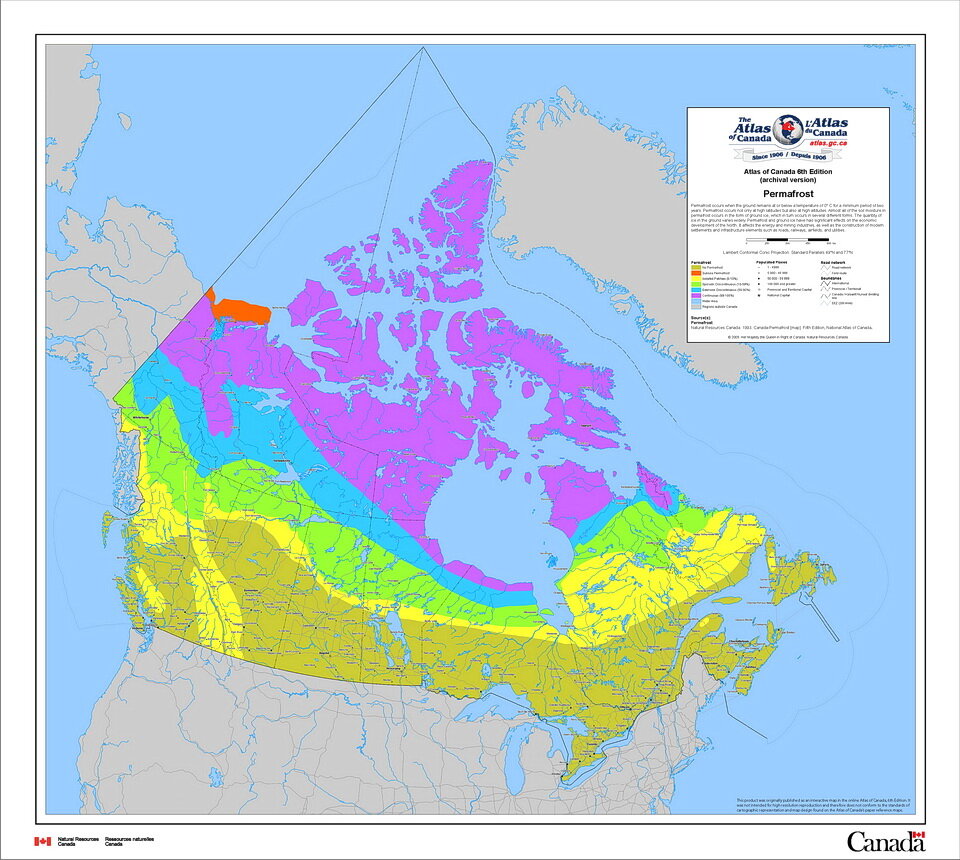

There are many pingos near Tuktoyaktuk, in the Northwest Territories. In fact, the Tuktoyaktuk peninsula is home to about 1350 pingos. This is the greatest number of pingos in a small area, in the world. Why is Tuktoyaktuk such a special place for pingos? Well, one important reason is the continuous permafrost that underlies the land in this area. Permafrost is critical important to pingo formation (Image 4).

Image 4: Distribution of permafrost across Canada. Image source: Canada-Permafrost Map

Recall that permafrost is defined as ground that remains frozen, and at a temperature below 0C (32F), for two or more consecutive summers.

You might be surprised to learn that permafrost occurs across Canada, in every Province and Territory except Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Image 4).

Pingo National Landmark / Pingo Canadian Landmark

To recognize and protect the large number of pingos in the Tuktoyaktuk area, the Pingo Canadian Landmark, also known as the Pingo National Landmark, was created in 1984 as part of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement. That agreement defined the cooperative management of the Pingo Canadian Landmark between the Government of Canada, the Inuvialuit Land Administration, and the people of Tuktoyaktuk.

The largest pingo in the Tuktoyaktuk area is called Ibyuk (Image 1 and 5). Ibyuk is about 1300 years old. It is Canada's tallest and the world's second-tallest pingo. It is 49 metres (160 feet) tall and stretches 300 metres (985 feet) across at its base. The upper half of Ibyuk pingo is growing upwards at between 2 and 3 cm (1 in) each year.

Image 5: The pingo located in the front is called the Ibyuk Pingo. It is located in the Pingo Canadian Landmark, near the community of Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada. Ice occupies the core of the pingo. The pingo is covered by an insulating blanket of tundra vegetation, which keeps the ice core from melting. The landscape in the foreground is typical tundra of this part of the subarctic. Image composed by Andy Fyon, June 18, 2019.

How Do Pingos Form?

To form a pingo, you need permafrost and water. Why water? Water has an unusual property. When water freezes, it expands by about 10%. That is why cans of pop or bottles of water expand and break when their watery contents freeze. The expansion of water when it freezes into ice is key to the formation of pingos.

We can model the formation of a pingo by filling a baggie with water (Image 6). When you freeze that water, the water expands as it transforms into ice and the baggie gets “fatter” (Image 7).

Image 6: We can model the formation of a pingo by filling, and freezing, a baggie filled with water. This water-filled baggie represents water-saturated lake-bottom sediments. Image by Andy Fyon.

Image 7: We can model the formation of a pingo by filling, and freezing, a baggie filled with water. The ice in this frozen baggie represents the ice core of the pingo. When it froze, the ice expanded in all directions. In the pingo world, the ice would have pushed upwards as it expanded, growing the pingo upwards. Image by Andy Fyon, April 15/21.

Now, let’s relate the freezing of water in a baggie to pingo formation. Many of the pingos in the Tuktoyaktuk area form in, and around, lakes or lakes that have drained (Image 8).

Image 8: A pingo in the Pingo Canadian Landmark located on the edge of a lake, near Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, Canada. This pingo appears to have formed on the edge of a partially drained subarctic lake. Photo by Andy Fyon, June 25/07.

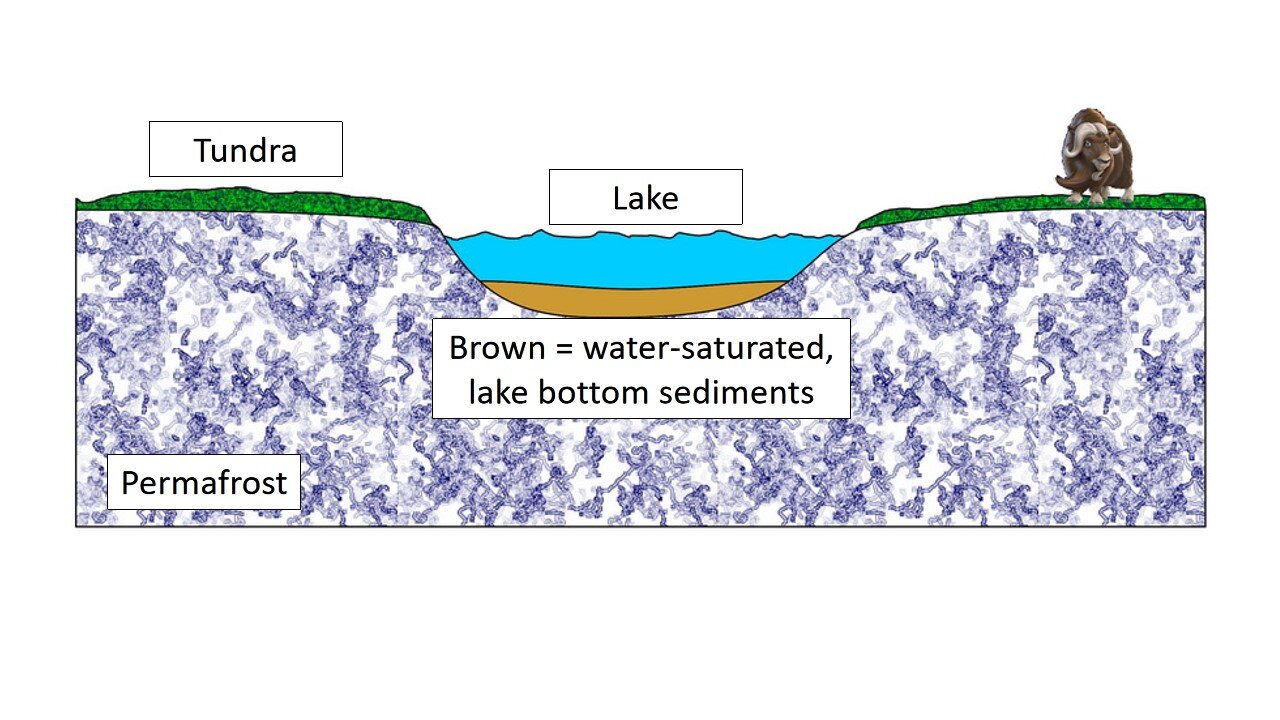

The lake bottom sediment, or muck, is saturated with water (Image 9).

Image 9: A cartoon of a tundra lake, developed on continuous permafrost. The brown coloured material represents water-saturated lake bottom sediments, or muck. Cartoon by E. Ginn, 2021.

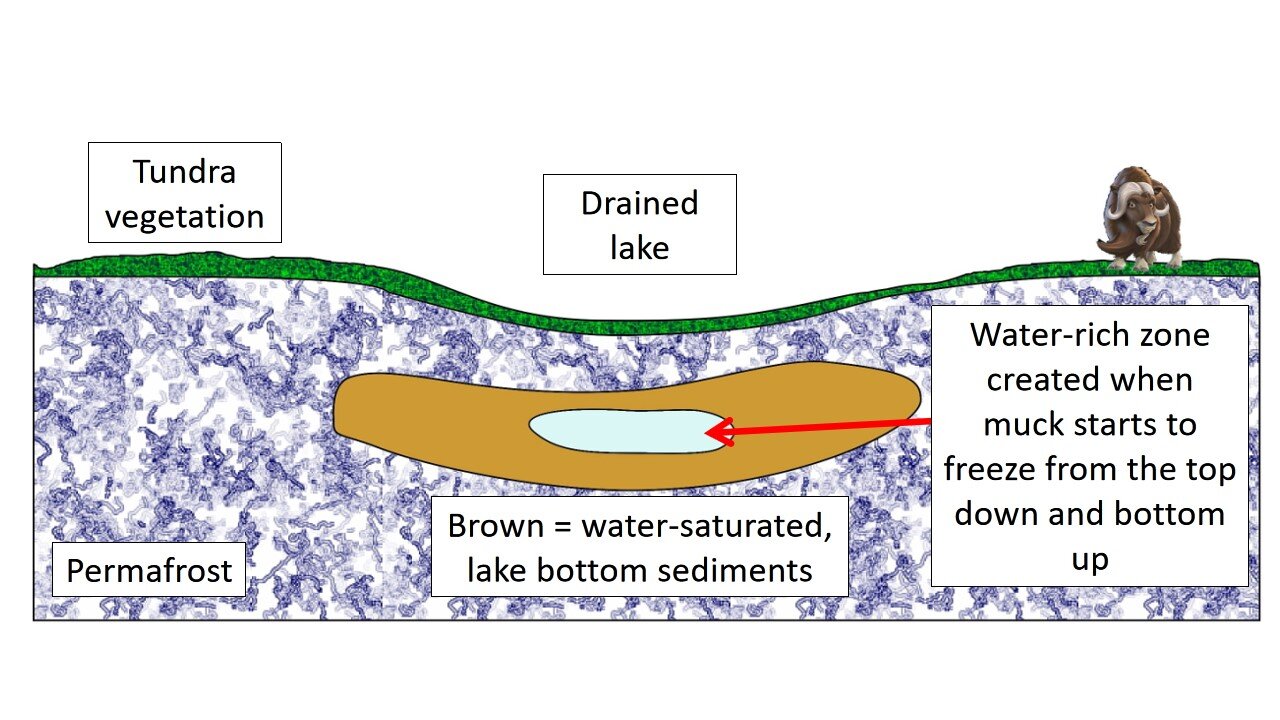

If the lake drains, or partially drains, and the climate of the area remains cold, two things happen ;

permafrost re-establishes itself on the bottom of the drained lake; and

the water-saturated, lake bottom sediment, or muck, starts to freeze from the bottom up, where the permafrost is located, and from the the top down, where the muck is exposed to the cold, arctic, winter air.

Water in the lens of water-saturated soil becomes trapped between the upper and lower freezing layers (Image 10).

Image 10: As the water-saturated lake bottom sediments freeze from the top down and the bottom up, pressurized water concentrates within the core of the lake bottom sediment. Cartoon by E. Ginn, April 18/21.

As the ground continues to freeze, that lens of water within the lake bottom sediment undergoes increasing pressure, called hydrostatic pressure. That hydrostatic pressure pushes the water up toward the surface, where it freezes to create the hill (Image 2). The ice lens can reach a height of 45 m (147 feet) in height! That is as tall as a 15 story building!

Do Pingos Grow Forever?

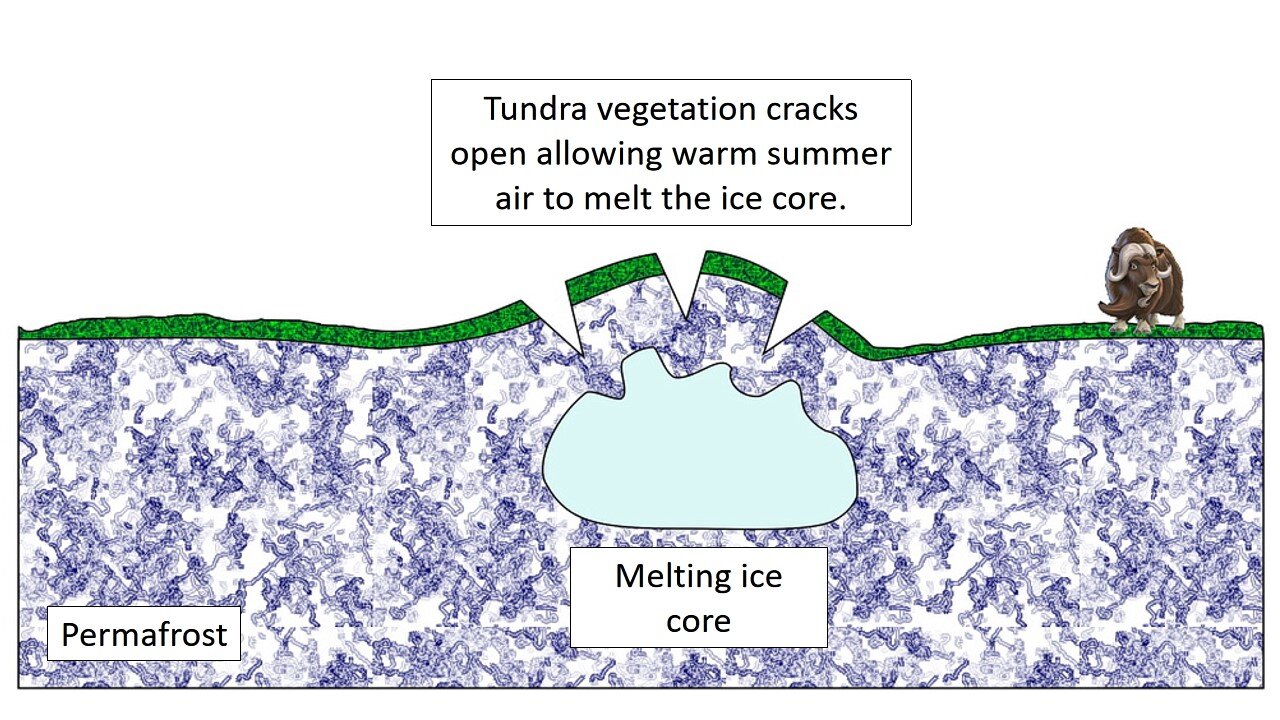

You might wonder if a pingo will grow forever? As you now appreciate, the ice core is critical to the growth and life of a pingo. That ice core supports the pingo. If the ice core is exposed to warm summer air, perhaps because the vegetation blanket was broken open by cracks, the ice core will thaw and the pingo will start to decay and get smaller (Image 11). If the ice core disappears, the pingo will collapse.

Image 11: If the vegetation blanket cracks open, warm summer air accesses and starts to melt the pingo ice core. Because the ice core supports the pingo, the pingo will collapse if the ice core melts. Cartoon by E. Ginn, April 18/21.

Sadly, this melting of the ice core may be affecting several pingos in the Pingo Canadian Landmark. For example, although Ibyuk pingo is still growing, the crown vegetation appears to show signs of cracking open (Image 12).

Image 12: View of Ibyuk pingo, Pingo Canadian Landmark, near Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories. The vegetation cover over the Ibyuk pingo ice core may be showing signs of cracking. If so, this breach of the vegetation blanket may be a threat to Ibyuk and may be provide access by warm summer air. That warm air may start to melt the ice core, which could lead to the collapse of the pingo. Photo composed by Andy Fyon, June 25, 2007.

Climate Change - Threat To Pingos

Recent warming temperatures, especially in the subarctic and Arctic regions, are attributed to warming global climate. That changing climate is a threat to the permafrost and therefore, to all pingos around the world.

So, I hope this short, simple science discussion leaves you with a better understanding of the amazing pingos in the Pingo Canadian Landmark, in the Tuktoyaktuk area. I trust you also appreciate their fragility. A warming climate is not the friend of the pingos.

More Pingo Images, Pingo Canadian Landmark

I share several photos below to illustrate some of the pingos that occur in the Turktoyaktuk area.

Have A Question About This Note?

April 20, 2021