Far North Friday #78: Science And Seven Generations

Have I reminded you that I know nothing about “the way” of the far north. What I may know, I’ve learned from a few books, but mostly from the mentors I had the privilege to work with, or listened to, across the far north.

Take science, for example. Many far north First Nation people taught me that their science world view, or system, is much more holistic compared to what I was taught during my “Western book” schooling.

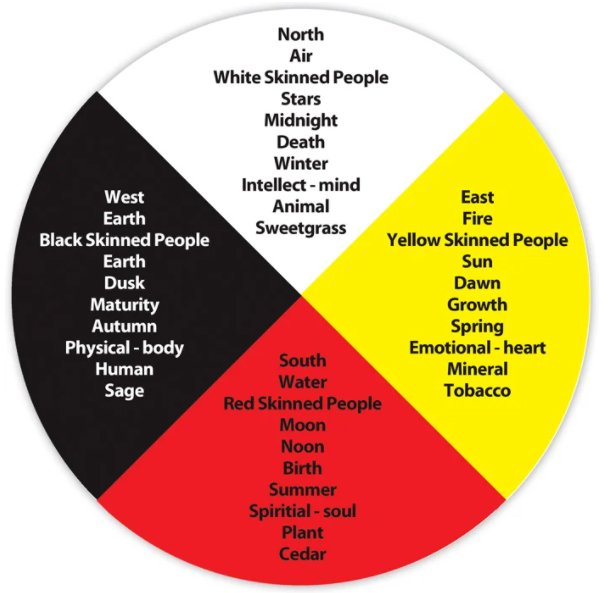

I learned that the Indigenous knowledge system “sees” and understands the world in four different ways (Photo 1), based on the "alignment and continuous interaction" between the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual realities: a) physical knowledge created by observation, measurement, and sensing the world; b) emotional knowledge and intelligence; c) spiritual knowledge; and d) intellectual knowledge created by mental processing and generating information. It was explained to me that these four ways of “knowing” are valid and important. They are different views used for different purposes and different questions. It's an holistic way of thinking about knowledge and for living in, looking at, and making decisions about the world.

Photo 1: One illustration of the indigenous Medicine Wheel, and the meanings of each quarter. Image from a post by Bob Joseph entitled “What is an indigenous medicine wheel?”.

Conversely, my formal science training, called by some as “book or Western science”, focused on physical knowledge created by observation and measurement and on intellectual knowledge created by mental processing. I never took a course on emotional or spiritual knowledge. I was not alone. I saw many “book scientists” state, or imply, that emotional and spiritual knowledge “don't count, don't matter, and are not real or valid knowledge.”

A wise First Nation person told me “Western book science” is a subset of the Indigenous science and knowledge world view. I thought about that comment for several months. They were correct! My science system is not better or worse, just a subset.

Each science system has powerful “ways of knowing”. When faced with a correct/incorrect question, the “Western book” scientific method, based on hypothesis formulation and testing, is an excellent approach. When faced with a complex question, being correct or incorrect becomes must be complemented by knowing what is right, what is meaningful, and what the implications are well into the future (e.g., seven generations). For such a complex question, requiring wisdom, the holistic Indigenous knowledge system is the tool of choice.

I sat at many tables working towards an important decision. I was drawn to consider what was “correct or incorrect”, notwithstanding those words are often contextual. In hindsight, it was equally important to ask what was right, what was meaningful, and what the implications were well into the future.

Some of you might saying “easy for you to say Andy. You are retired and can say what ever you want.” That is true. I appreciate your challenge, but I began to develop a simple test. Would I ask my grandchild to live the consequence of my decision? Too subtle? OK, would I ask my grandchild to drink the water effluent from a development site? If the answer is “no”, then I have more thinking to do about what is right, meaningful, and with good implications, as an expanded science world view.

More Information:

These thoughts are not mine. They belong to the far north people who took the risk and time to help me see the world differently through my one good eye.

If this thought interests you, or confuses you, you might listen to an interview with bryologist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer or read a short note by Bob Joseph and watch his 3 minute video on the Medicine Wheel, which is the source of the image I used. For your consideration.

You might also read the note entitled “Knowledge keepers: How Western science and Indigenous knowledge intertwine”.

Andy Fyon, March 15. 2022; Facebook March 11/22