Ice Age: The Geological Story of Eskers

Figure 1: The esker is the long snake-like feature that runs from the bottom to the top of the photo southwest of Cat Lake community. Photo by Andy Fyon, morning, December 10, 2013.

What Is An Esker?

An esker is a long, narrow ridge, the snakes across the land (Figure 1). The esker is made of layers of sand and gravel. It marks the location of a tunnel that developed beneath a glacier.

The esker is one of the most easily recognized landforms that formed during an ice age, while a glacier covered the land. In flat boggy areas, eskers stand as high ridges and serve as vantage points, dry route ways, and areas for animal dens.

Eskers were formed by the glacier. But how? In this note, we will explore eskers in more detail and learn how they formed.

Let Us Imagine Ontario - A Land Of Ice

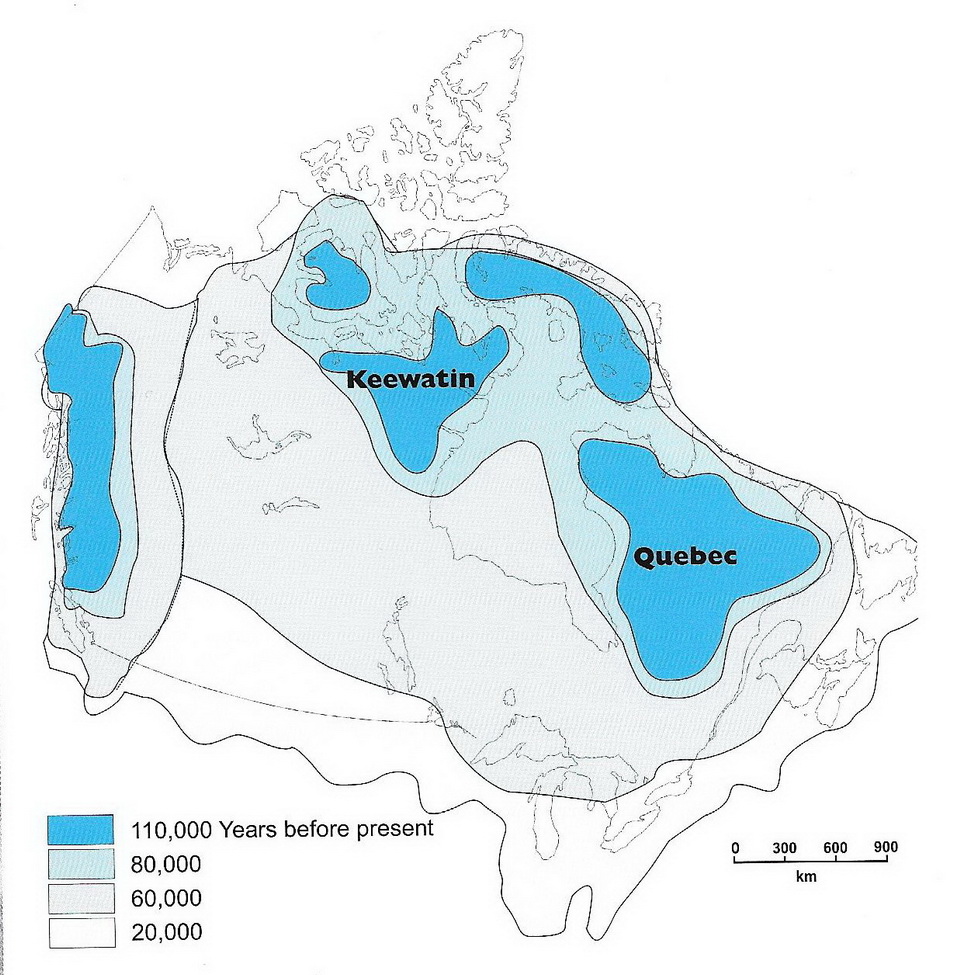

Between 100,000 and 80,000 years ago, all of Ontario was covered by a glacier - a thick sheet of ice (Figure 2). A lot of ice covered the land. At its peak, the glacier is estimated to have been up to 2 kilometers thick.

Figure 2: Cartoon that shows the extent of the glacier during the last ice age, which started about 2 million years ago and ended about 13,000 years ago in the area we now call Bonnechere Provincial Park. Images constructed from data provided by Arthur S. Dyke (2004).

The land would have looked something like the photo below (Figure 3)! Of course, there were no mountains in Ontario 20,000 years ago, so just ignore the mountains.

Figure 3: This is a photograph of an alpine glacier in British Columbia. While not directly analogous to the continental glacier that covered all of Ontario 2 million years ago, the image does illustrate the extensive cover of ice that is possible during a period of time when glaciers covered almost all of Canada. Photo by Andy Fyon, August 5, 2008.

The Geological Legacy of Glaciation

Much of the unconsolidated material that covers the rock today was deposited by this glacier. Some landforms were created as the glacier moved over the land. Other landforms were created as the glacier started to melt and roaring rivers were created by the melting ice. Several cycles of glacier growth followed by glacier melting occurred during this time of the last ice age.

When the climate warmed about 20,000 years ago, and the glacier started to melt. Ice-free land appeared in southern Ontario as the glacier started to melt about 18,000 years ago. This was the beginning of the end of the last great ice age that covered Ontario. Eventually, with continued melting of the glacier, Hudson Bay became glacier-free between 8500 and 9000 years ago. This was the end of the great and most recent ice age.

A lot of water was produced by the melting ice! That water is called glacial meltwater. That glacial meltwater had a profound role in shaping the surface of the land beneath the glacier and across the ice-free land. Some of the roaring meltwater rivers flowed across ice-free land. Other meltwater rivers actually flowed beneath the glacier.

Many eskers were formed by that glacial meltwater from a meltwater river that that flowed BENEATH the glacier or along ice-walled trenches on top of the glacier!

Eskers are only one of the legacies of the last ice age.

Role Of Glacial Meltwater

Glacial meltwater rivers create eskers. The glacial meltwater is full of debris. When the flow of this glacial meltwater river decreases, the debris is laid down on the floor of the tunnel. This material is called sediment. Meltwater is created when the glacier melts or when the glacier neither grows or contracts - that is, the glacier becomes stagnant.

To create an esker, you need a lot of sediment and a huge volume of meltwater flow. Melting glaciers meet those conditions.

What Is An Esker Made Of?

An esker is usually made of sand and gravel. The sand and gravels are generally clean - meaning, the meltwater washed away all the very fine clay-sized and silt-sized materials. The sandy materials may show horizontally beds or may show the geological feature called cross-bedding. Sometimes, there is no evidence of any type of layering. These different layers represent deposition of the sand from water under different conditions.

What Is The Shape Of An Esker?

There is no universal description of an esker. While eskers are generally long and narrow ridges, they do vary in shape and size. Most eskers snake across the land. They are sinuous. Eskers generally are a few meters to several tens of meters in height. A single esker may run across the land for several kilometers, although most eskers are shorter or even discontinuous. The top of an esker may be broad and flat-topped, with a single crest or with parallel ridges. Sometimes, a esker may actually travel up a slope. That is an additional indication that the meltwater moved under pressure, in a tunnel, beneath the glacier.

A discontinuous esker forms because the sediments are not laid down along the entire length of the tunnel beneath the glacier. An esker may be eroded by a later influence of meltwater rivers or by the action of lakes that formed after the ice melts.

How Are Eskers Used?

Foxes, wolves and other small animals makes the dens in the sandy esker material.

Other animals use the esker ridges as access corridors, especially across lakes or boggy land (Figure 4).

Figure 4:The dark wiggly ridge across this frozen lake is an esker. Animals and humans might use this height of land to cross the lake and as a place to get a good view of the surroundings. Photo composed by Andy Fyon, from an aircraft at about 20,000 feet, between Lansdowne House and Webequie, May 17/14.

Because the esker materials are clean, meaning they are relatively pure sands and gravels that are free of fine-grained materials, eskers are often used as a source of aggregate and construction sand.

Buried eskers can serve as excellent groundwater aquifers - material that traps rain and snow melt over the ages. The clean sediments means the the groundwater is suitable for drinking water.

Eskers also make excellent road base for either all season or winter roads because the material is high, dry and well drained, so frost upheaval is less of an issue (Figure 5).

Figure 5: An esker south of Timmins, Ontario, is being used as a source of road construction material. Photo by Cam Baker, formerly of Ontario Geological Survey.

Summary

Eskers are one of the more easily recognized landforms that were formed by glacial meltwater rivers. Those rivers flowed beneath glaciers in tunnels or within ice-walled trenches on or beside the glaciers. Eskers are made of sand and gravel. The esker snakes discontinuously across the land as a narrow ridge.

Animals use eskers for their dens, as access corridors across boggy land. Eskers are also a source of aggregate, make excellent road beds, and buried eskers can be important sources of clean groundwater suitable for drinking.

Some Sources of Information

There are several excellent summaries of pothole formation in Ontario, including:

a) Eskers

b) Esker - The Canadian Encyclopedia

b) Arthur S. Dyke (2004): An outline of North American Deglaciation with emphasis on central and northern Canada, contained in Quaternary Glaciations - Extent and Chronology, Part II: North America, edited by J. Ehlers and P.L. Gibbard, Development in Quaternary Science, 2.

Have A Question About This Note?

Andy Fyon, Nov 29/16; Dec 3/16; April 6/17.